Reality Check on AI Hype: How AI Slowdowns Software Development Velocity

A first-of-its-kind research outcome from the Model Evaluation & Threat Research (METR) team.

In the ongoing wave of AI optimism, one new study has caught the attention of the software engineering world by doing the unthinkable: challenging the assumption that AI assistants improve developer productivity and thus, killing the AI hype.

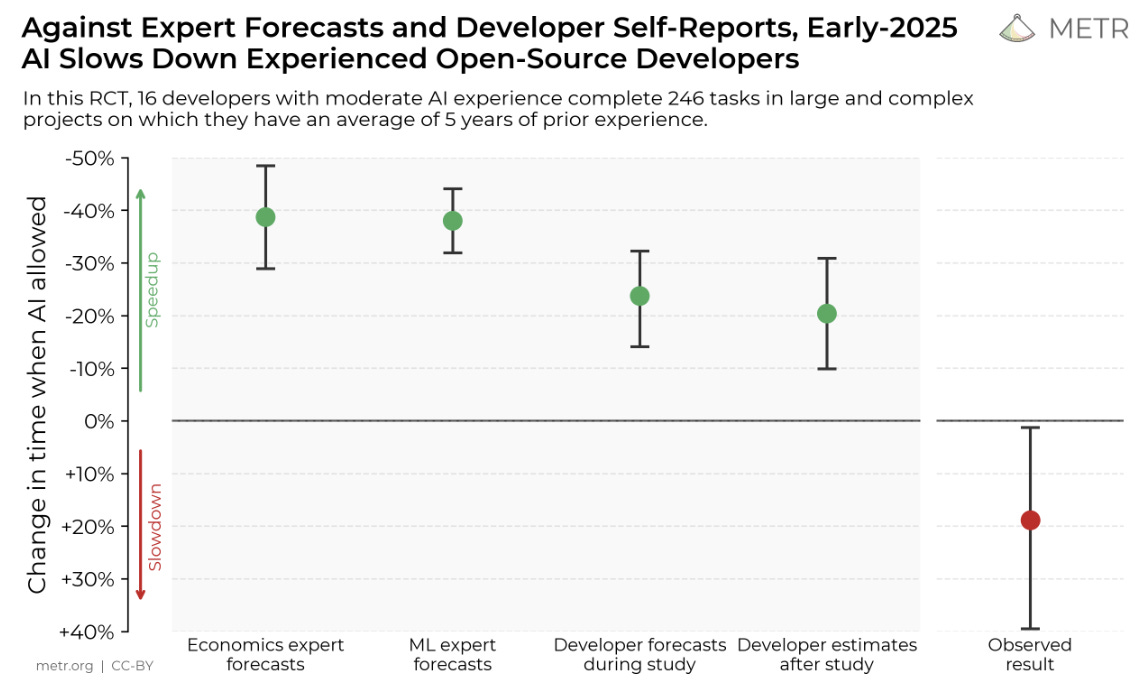

On July 10, 2025, METR (Machine Evaluation and Testing for Responsibility) published the results of an experiment that evaluated the impact of AI coding tools on experienced developers working on complex real-world tasks. The findings weren’t just surprising - they were completely contradictory for those banking on AI to “10x” software delivery.

According to the study, developers using AI assistants were significantly less likely to complete their assigned tasks successfully than those working without AI help. The implication isn’t that AI is bad for coding. Rather, it’s a sobering reminder that how we use these tools, and in what context, matters far more than many organizations currently acknowledge.

Understanding the Study

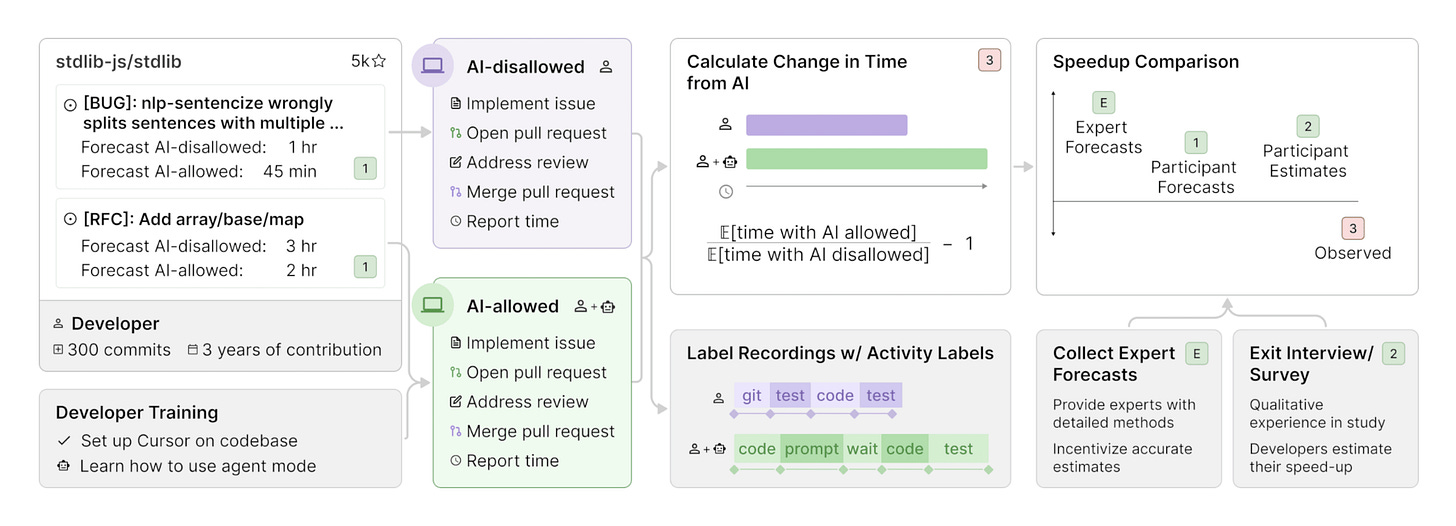

The METR research focused on a simple, real-world question: can AI tools like GPT-4 actually make experienced developers more productive on non-trivial coding problems?

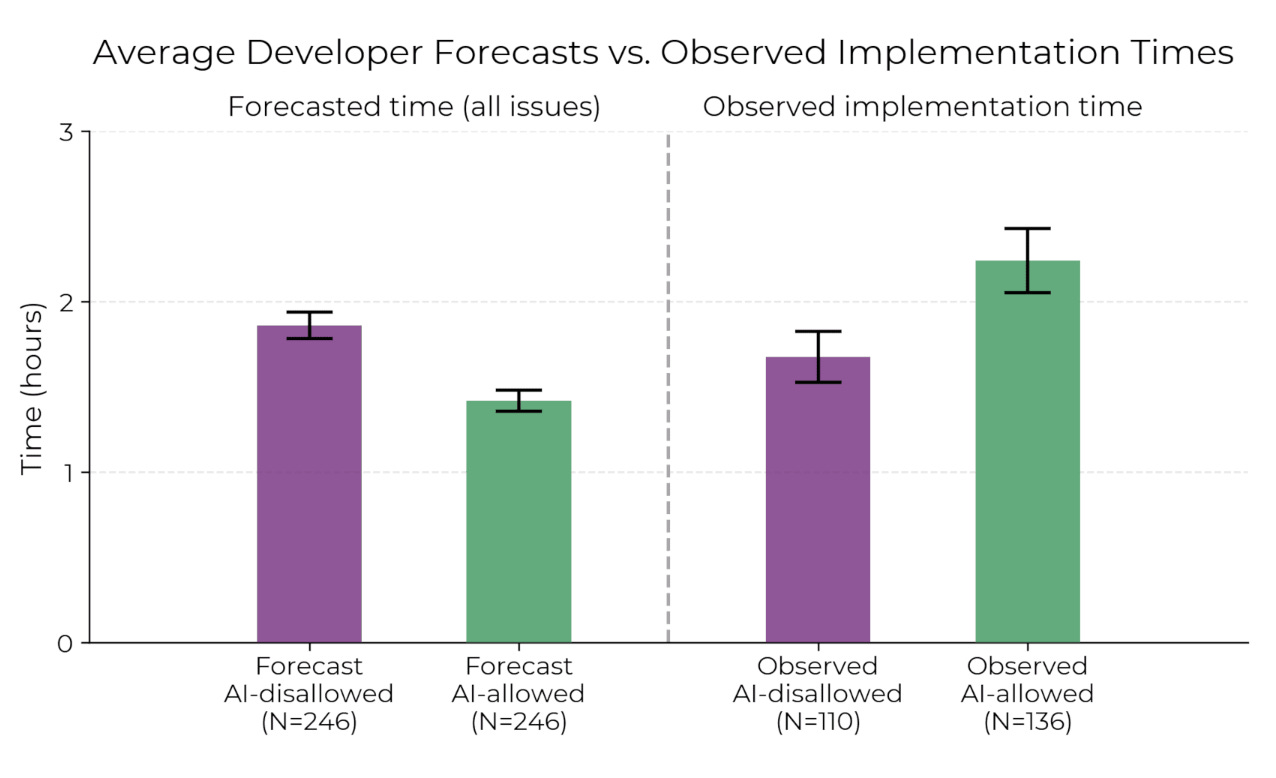

To find out, the team recruited a group of experienced open-source developers. Each participant was randomly assigned to either use an AI assistant or proceed without one. Their task was to resolve a real issue pulled from a mature open-source codebase. Each person had up to four hours to complete their assignment, with success measured by whether their pull request was correct and accepted.

What happened was striking. Developers with AI access completed fewer successful tasks than those without it—by about 20 percentage points. While the AI-assisted group often wrote and submitted more code within the time frame, they were more likely to introduce logic errors or misunderstand the problem altogether. Speed came at the expense of quality, and the AI did little to help developers verify or reason through their solutions.

Interrogating the Methodology

As with any study, it's worth asking how generalizable these results are. METR's methodology was solid, but not without limitations that should be considered by teams evaluating how this research applies to their own use of AI.

First, the participant pool consisted of experienced open-source contributors. This is both a strength and a weakness. On one hand, these are capable developers who understand version control and community norms. On the other hand, their workflows may differ meaningfully from engineers in a startup or enterprise environment where collaboration, mentorship, and tooling differ dramatically.

Second, each participant tackled just one problem, and within a constrained four-hour window. In real-world settings, developers don’t always ship in a single session. Problems evolve over time, collaboration increases clarity, and solutions are often reviewed and revised through pair programming or code review. AI may well add value in those longer, more iterative cycles.

Third, the study didn’t account for familiarity with the AI tool. If participants were new to GPT-4 or hadn’t spent time learning how to engineer prompts, interpret completions, or validate output, they may have been operating at a disadvantage. In other words, they were using a very sharp tool without being trained to handle it safely.

Fourth, our n count for this study was merely 16 developers. To be fair, running an experiment of this nature en masse would be an expensive ordeal. However, it is worth calling out that statistically speaking, we aren’t dealing with a lot of data points.

Finally, incentive alignment plays a subtle but important role. These were task-based, paid participants—not team members with skin in the game. That lack of long-term accountability may have encouraged quick wins rather than sustainable solutions.

None of this invalidates the results. But it does mean we should apply them thoughtfully, not universally.

What This Means for Engineering Teams and Leaders

The most important takeaway from the METR study is that AI-assisted development is not a guaranteed productivity boost. In fact, for certain types of work, it may be a liability.

Engineering leaders need to understand that the promise of AI isn’t about replacing developers—it’s about augmenting them. But augmentation works best in environments with the right scaffolding: clear documentation, robust testing, strong code review culture, and developers trained to engage critically with AI output.

The risks of over-relying on AI include more than just bad code. Left unchecked, AI-assisted development can lead to a false sense of speed, a degraded understanding of core systems, and an erosion of engineering judgment. Teams may move faster in the short term while accruing hidden technical debt they won’t recognize until it’s too late.

That makes it critical for leaders to identify where AI tools should be deployed and where they may do more harm than good.

Where AI Coding Tools Tend to Help—and Where They Don’t

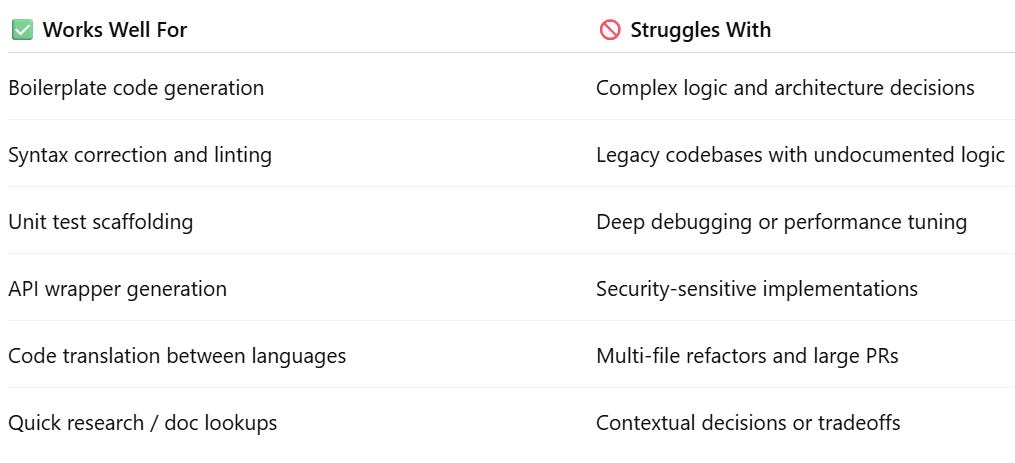

Based on the METR findings and broader industry patterns, AI assistants tend to excel at tasks that are well-defined, repetitive, or heavily dependent on pattern recognition.

Developers gain real leverage when using AI for generating boilerplate code, scaffolding unit tests, translating syntax between languages, or building simple wrappers around APIs. These are low-risk, high-volume tasks where automation shines and correctness is often easy to verify.

In contrast, AI assistance begins to break down in areas where success depends on judgment, domain knowledge, or architectural foresight. Debugging complex systems, navigating unfamiliar legacy code, planning multi-file refactors, and making performance or security decisions are all areas where human reasoning still outperforms language model predictions.

In practice, this means teams should integrate AI coding tools in targeted ways—automating the repeatable while doubling down on human oversight where context matters.

A More Nuanced Future

The METR study is not a repudiation of AI in software engineering. It’s a necessary correction to an overly simplistic narrative.

In the rush to deploy AI copilots across every terminal, some teams have lost sight of what software engineering actually is: an iterative, collaborative problem-solving process grounded in context, tradeoffs, and communication. No AI tool—no matter how advanced—can fully grasp all of those elements today.

For organizations that want to harness the power of AI while avoiding the pitfalls, the answer lies in building thoughtful systems. That means investing in developer training, maintaining high code quality standards, encouraging pair programming and review, and making sure that AI is used as a sounding board, not a crutch.

Because the most dangerous code isn’t just wrong—it’s code written confidently by a machine, and merged by a developer who didn’t stop to ask why.

I encourage you all to read the study: https://metr.org/blog/2025-07-10-early-2025-ai-experienced-os-dev-study/